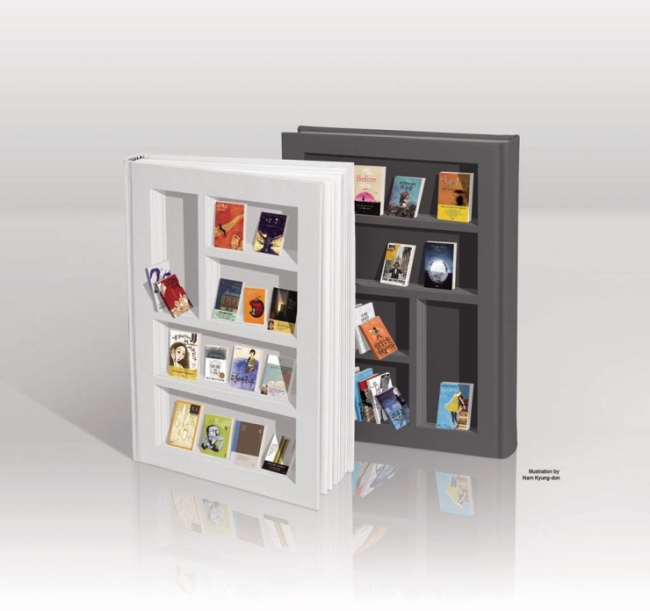

The story of Korean fiction: Proud tradition, humble present

How homegrown novels have become a rare find on best-seller lists

By 이선영Published : Oct. 23, 2015 - 18:27

If you’re reading a novel from Korea’s best-seller lists now, chances are that it’s not written by a local author.

In this country, with a rising global cultural profile and an ambition to rise even further, fiction, the ultimate art of storytelling, is fading. Or more precisely, the serious, high-caliber, literary fiction that Koreans refer to as “pure” literature is fading.

Local readers’ appetite for homegrown novels is dwindling amid a fundamental decline in an interest in books, while writers are failing to produce stories that re-engage them, experts say.

Signs of a crisis are hard to miss, starting from the best-seller lists.

“Korean fiction is rare to spot in the best-seller section this year,” said Kim Hyun-jeong, a spokesperson for Kyobo Bookstore, the country’s largest bookseller.

At Kyobo, sales of Korean novels -- whether literary or commercial -- have dropped 28 percent so far this year from the same period in 2014, she revealed.

A look at last week’s top-20 book list, compiled by the local publishers’ association, shows what Koreans are reading now: Swedish sensation Fredrik Backman’s “A Man Called Ove”; Harper Lee’s “Mockingbird” sequel “Go Set a Watchman”; Japanese thriller stalwart Keigo Higashino’s “The Miracle in the Grocery Store”; and Andy Weir’s “Martian,” to name a few.

The sole Korean fiction in the best-seller territory is Kim Jin-myung’s “Letter War,” released in July this year, holding the No. 5 spot in the ranking that encompasses both fiction and nonfiction. Before Kim’s book, which local critics consider “not literary enough,” the weekly tally had not had a Korean fiction entry for several months.

“Korean readers, who once found it difficult to relate to translated works, appear to be enjoying them more, thanks to their increased understanding of foreign cultures, as seen in the popularity of U.S. TV dramas here, as well as the burgeoning rank of qualified translators,” explained Lee Kyeong-jae, professor of Korean Literature at Soongsil University in Seoul.

Korean fiction’s poor performance this year is also attributed to the absence of new releases from the country’s top-selling novelists such as Shin Kyung-sook, Gong Ji-young and Hwang Sok-yong.

What’s ironic is that while Korean fiction is losing its appeal for contemporary Koreans, the world is beginning to recognize the depth and richness of Korea’s literary tradition, as seen at last year’s London Book Fair, where Korea took center stage.

In 2011, novelist Shin brought hopes of Korean fiction’s global breakthrough, with her first English-translated novel “Please Look After Mom” becoming a New York Times best seller. Her achievement lost shine in June this year, however, after she admitted to plagiarism in her earlier work. The plagiarism case, raised by a fellow Korean novelist, led to a heated debate on how Korea’s literary world is shaped by those with vested power, namely major publishing houses and literary stalwarts like Shin that they represent.

To Lee O-young, a renowned writer-critic who served as the country’s first culture minister, Korean fiction’s humble standing today, in spite of its proud tradition, is because of its failure to adapt to the changing times, or the changes in the Korean psyche.

“Literature, in the past, was not mere literature. It (in its own way) confronted the military dictatorship, as the container of the voices of that time,” he said in a recent interview.

Today’s readers are not living under Japanese occupation, the Korean War or the democratic uprisings of the ’80s. “They have different desires. Literature now is failing to respond to them,” he said.

Some say the reason for this Korean problem is more universal. They say the crisis of literary fiction, as compared to commercial or genre fiction, is not a phenomenon confined to Korea, as the audience in this digital age lean toward “light” reading.

In fact, outside the “pure" literature territory in Korea, writers of thriller, romance or sci-fi genres have been gaining ground in recent years, utilizing emerging platforms such as e-books and Web novels -- characterized by serial publishing on the Internet or mobile phone platforms. New generations of high-caliber writers are emerging as well, crossing the line between “pure” and commercial fictions, although their major breakthrough is yet to come.

“If you look at foreign fiction titles that are selling well in Korea, they often fall in between literary and genre fiction. They have that commercial appeal of genre fiction, without sacrificing the depth and style of a literary work,” said Suh Young-in, a literary critic.

By Lee Sun-young

(milaya@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)