Economy

Strengthening won weighing on exporters

[THE INVESTOR] The steep appreciation of the won against the dollar in recent months is weighing on Korean exporting firms, with the country’s currency authorities not positioned to curb it.

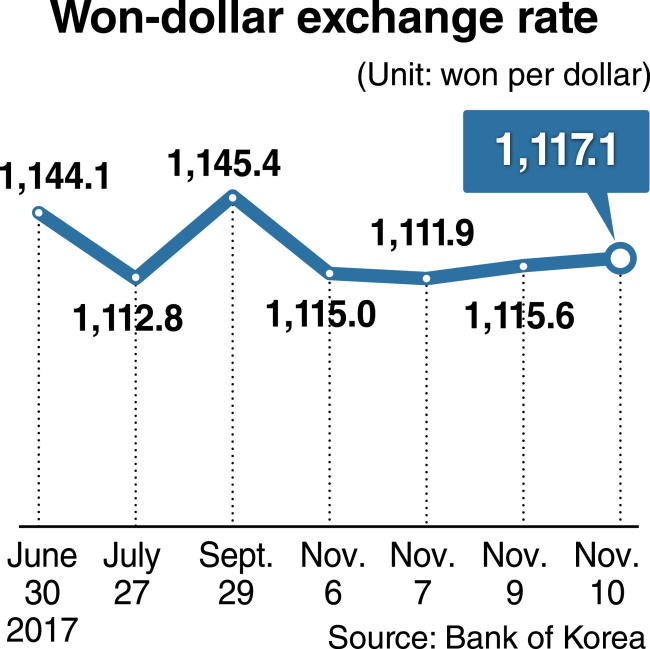

The won-dollar exchange rate strengthened nearly 3 percent from October to a yearly low of 1,111.9 won per dollar on Nov. 7. It slightly weakened in the following trading days to close at 1,117.1 won on Nov. 10.

|

The recent appreciation of the Korean currency against the dollar comes as the greenback strengthens against the Japanese yen and other major currencies.

The won has appreciated against the yen almost 4 percent since October to fall below 980 won per 100 yen for the first time in two years.

“The won-dollar exchange rate may tumble below 1,100 won, now regarded as a psychological line,” said Choi Bae-geun, a professor of economics at Konkuk University in Seoul.

He noted the strengthening of the won would particularly weaken the price competitiveness of Korean export goods vying with Japanese products in overlapping markets around the globe.

A study by the Hyundai Research Institute, a local private think tank, estimated a 5 percent depreciation of the yen against the won would result in a reduction of 1.4 percent in Korea’s exports, dragging down its economic growth rate by 0.27 percentage points.

At the outset of this year, the Korean currency was expected to continue to weaken against the greenback, as the annual average won-dollar exchange rate rose from 1,050 won in 2014 to 1,130 won in 2015 and 1,160 won last year.

Behind the recent rise in the value of the won is a complex set of internal and external factors.

The Bank of Korea last month announced the country’s economy grew 1.4 percent from the previous three months in the July-September period, nearly double market expectations.

Asia’s fourth-largest economy has continued to extend a streak of monthly current account surpluses, with foreign investors having turned to net buyers of Korean shares.

Seoul and Beijing recently agreed to end the dispute over the former’s hosting of an advanced US missile defense system, raising expectations that China will lift retaliatory measures that have inflicted huge losses on Korean businesses.

The won seems set to continue to be strengthening amid an easing of tensions on the Korean Peninsula, coupled with the prospect of the BOK moving to raise its benchmark rate, which has remained at a record low of 1.25 percent since June last year.

Finance Minister Kim Dong-yeon said early this month the government “is keeping a close watch” on what he described as the “excessive” pace of the won’s appreciation.

His remarks, which marked the first verbal intervention in the currency market since President Moon Jae-in’s administration was launched in May, helped the won-dollar exchange rate rebound slightly before falling again.

What troubles currency authorities here is that they have no effective means beyond verbal intervention to cope with the further strengthening of the won.

Any move that could be seen as a direct involvement in the currency market, such as the central bank’s persistent buying or selling of foreign currencies, would invite the US Treasury to designate the country a currency manipulator.

Korea is on the Treasury’s monitoring list, having met two of the three requirements for being labeled as a manipulator by piling up large amounts of current account surpluses and trade surpluses with the US.

“You could have a fairly accurate grasp of the central bank’s moves by looking into changes in the level of foreign currency reserves,” said a BOK official on condition of anonymity.

Issuing bonds to stabilize the exchange rate is a less direct but more costly method.

The government’s issuance early this year of foreign exchange stabilization bonds worth $1 billion costs 30 billion won ($26.7 million) in annual interest, though it carries a record low rate of 2.871 percent.

Experts here say efforts to win more understanding from the US are needed to expand room for coping with fluctuations in the value of the won.

They note Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration has pushed for policies to keep the yen weaker over the past five years under an apparent acquiescence of Washington.

“Gaining some degree of acceptance (from the US) regarding market intervention would be the best way to reduce risks from fluctuations in the exchange rate,” said Sung Tae-yoon, a professor of economics at Yonsei University in Seoul.

It could help make the US more accommodative for Korea to take more active measures to reduce trade surpluses with the world’s largest economy.

On a positive note, the steep appreciation of the won might contribute to Korea’s gross national income per capita touching the elusive target of $30,000 this year.

Local economic research institutes estimate the country’s per capita GNI to be somewhere between $29,500 and $29,800 in 2017, on the assumption that its economy grows 3 percent and the won-dollar exchange rate averages 1,130 won.

Even if the economy records zero growth in the fourth quarter of the year, the annual growth rate would still reach 3.1 percent, according to BOK analysts.

Under this condition, Korea is likely to see its per capita GNI exceed $30,000 this year, if the annual average won-dollar exchange rate falls below 1,120 won.

By Kim Kyung-ho/The Korea Herald (khkim@heraldcorp.com)